Luckless Yamsi

The Failure of Hubris to Account for Reality; for Lack of an Answer

It’s 11:39 pm, 14th April 1912, and, as far as Western civilization is concerned, the modern dream still exists. A vessel of pure security and pilgrimage is heading for New York, a vision of engineering excellence, and the North Atlantic Ocean is as calm as a millpond, its temperature the coldest in recorded history. Yet, in just one minute at 11:40 pm, lookout Frederick Fleet, aboard the RMS Titanic will call the bridge and inform them of an “Iceberg right ahead,”. The next 37 seconds must have felt like a seemingly infinite expanse of time for those watching. At first glance, it appeared as if the ice had glided past, appearing to passenger Edith Rosenbaum as a “ghostly wall of white”. But history always wins. So here, some 112 years on, stood atop countless books, films, documentaries, and a 46,000-ton shipwreck, we know for certain that the unsinkable is, in truth, sinkable.

I consider the Titanic's construction, launch, and maiden voyage to be the peak of modernity, both in ideal and material terms. Its collision with the iceberg was a collision of Spenglerian fate, marking the crux of our cyclical journey and the beginning of our descent down the other side. A beginning, in no uncertain terms, of uncertainty. I mean this in no derisive or cynical manner, and Gareth Russell’s book The Ship of Dreams: The Sinking of the Titanic and the End of the Edwardian Era already goes someway in detailing the ship’s descent as twofold, of both vessel and ideals. And yet, captured in this singular tragedy is all one needs for an understanding of the fractured modern mind, unable to heal itself since, forever haunted by the specter of a ship residing 2.3 miles beneath the ocean surface, an artifact of an event seated in our collective unconscious as a reminder of failure as an ever-present possibility, if not eventuality. The Titanic, the ‘Ship of Dreams’, caught in the recurrent memory of everything it shouldn’t have been. One may ask why it is the sinking of the Titanic is so famous, especially considering there is a mass of other tragic events to analyze via the lens of hubris. I think the important, hidden question is, what else was it that sank alongside the Titanic that night to chain it so firmly in our collective memory?

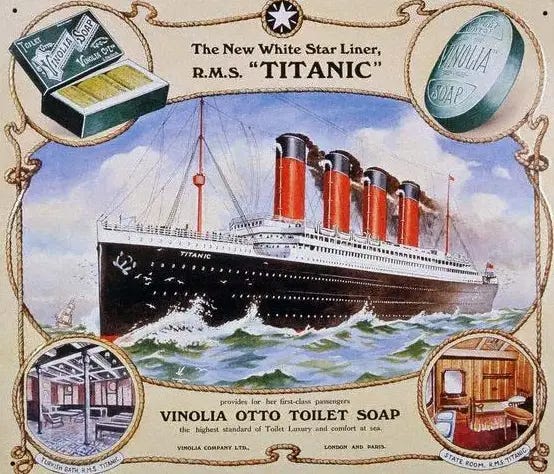

Departing from Southampton with the intention of docking in New York. Primarily a pilgrimage of prosperity for those in third and second class, and a journey of fascination and luxury for those in first, the maiden voyage of the Titanic was an archetypal modern dream, sailing off from poverty to arrive at the feet of the Statue of Liberty, all the while aboard one of the most astounding and exuberant creations to ever grace the planet. A time when such seemingly archaic virtues as explicit chivalry, honor, and prestige reigned. When class was far more than an idea and led to segregation of groups. When the last traces of the Victorian sensibility were visible for all to see. And, as such, a time when the values of the Enlightenment, the industrial revolution, and reason’s supremacy acted as a foundation for all endeavors. A time then, when advertising a ship as ‘unsinkable’ is not necessarily surprising. Even though many will be quick to claim that proclamations of the Titanic’s ‘unsinkable’ nature didn’t catch on until after the sinking, in my opinion, such statements merely bolster the wilful ignorance of the notion itself. “We place absolute confidence in the Titanic. We believe that the boat is unsinkable.” stated Philip Franklin, Vice-President of White Star Line, owners of Titanic, a mere 12 hours after the sinking. Though it is unprovable as it is connected to cultural subjectivity, it appears that the matter of unsinkability was just a marketing ploy, but only so because it was accepted without thought for its verification.

We may grin at such (seemingly apparent) hubris now, but it was not simply a pragmatic matter of engineering or shipbuilding that was in mind when one spoke of the Titanic as ‘unsinkable’, no, it was a social, historical, and abstractly chivalrous certainty for those of the day. One can reference any of the texts in the short bibliography at the end and realize that what began as a common marketing ploy slowly transformed into a statement of the highest, unconscious certainty, that therein quickly became a reality for many of its passengers and crew alike. It is this confrontation with reality that the sinking of the Titanic truly exhibits. The unsinkable is sinking being the witnessing of either an oversight/error or of one’s astounding ignorance and hubris, and though often considered the hubristic modern event, the former reality is closer to the truth, with a large helping of pure disbelief thrown in.

As to how this all unfolded is critically important. From our position in the future, a quick gloss of the facts of the sinking appears to make it clear that the tragedy could have been avoided if there had been more lifeboats. The quick comment regarding the sinking is the distinct (not enough for everyone onboard) lack of lifeboats, and yet, the Titanic (and its owner White Star Line) were not only entirely in line with current regulations but actually exceeded them. Further, and arguably more importantly for the point of this piece, even if the Titanic had enough lifeboats to accommodate 100% of its passengers and crew, the large majority of people still would not have been saved. Why would this be the case? The pragmatic answer is possibly logistics. Of the 2 hours and 40-minute sinking window (which Smith approximately knew via the ship’s designer Thomas Andrews), it took Captain Smith roughly 40 minutes to make an executive decision to abandon ship and another 20 minutes for crew members to be ready to launch passengers. Yet the idealistic answer is arguably one of the aforementioned potential hubris. As the ship slowly tilted its way into the sea, a large number of passengers at this early stage refused to enter the lifeboats for a multitude of reasons. The primary motive was that the Titanic was unsinkable and therefore it made no sense that such an event could, or more importantly, can be happening. Why would one leave a ship that cannot sink only to get into a small lifeboat and float out into a black abyss?

In retrospect, the decision to remain on the Titanic appears absurd, borderline insane, even. Yet a mass of various statements attest to the continuing denial of reality that the Titanic was more than a ship, it quite literally was unsinkable, a testament to reason itself. As such, at roughly some time after 1:10 am (when the Titanic would have looked like the image below - from here) Fourth Officer Boxhall, stood at the bridge and commented to Captain Smith “Captain, is it really serious?” to which Smith replied, “Mr Andrews tells me, that he gives her from an hour to an hour and a half.”

A mixture of disbelief and fear to be sure, but the hubris surrounding the sinking is far more multifaceted than a clear-cut matter of Promethean arrogance. This is not a tale of a risky venture alike the Wright Brothers first flight or the Moon Landing, wherein the territory and technique are both unexplored. The story of the Titanic is one in which near enough everything—contextual to its day—was perfectly fine, perhaps excessively so. The ship passed all its inspections and sea trials, White Star Line went above and beyond regulatory requirements, there was no more seasoned captain than that of Smith, the Titanic itself was another iteration in a long line of ‘last words’ in shipbuilding, and the collision with the iceberg itself was such a unique matter concerning anomalous weather patterns that no one is really to blame.

The much-debated hubris regarding the Titanic, then, is not a specific matter of overwhelming pride about the ship itself but concerns a flagging enlightenment sensibility of putting complete trust into the fruits of reason. Everything was done correctly as per all instructions from the best of the best of the day, and yet the ship still sank. Seen in this light, I feel the sinking reveals a peculiar banality inherent within the myth of Prometheus. Prometheus brought the destructive power of fire, and more generally technology (“techne”), to man, for which Prometheus was condemned to perpetual torture by the gods. Yet, Prometheus was smart and a champion of humanity, he wanted us to sore and not be subordinate to the ‘greater’ Gods. The Promethean fire soared, the human aspect erred, and the synthesis of the two ended in tragedy. A strange equilibrium that only humanity manages to reach. From this, I wish to look at the question I opened this piece with, namely, what was it that sank along with the Titanic that night?

The scenes, as described in Walter Lord’s seminal A Night to Remember are intensely vivid. The early hours of the morning, a moonless sky, and an absolute black expanse in every direction (barring a few tiny lights). The temperature of the air was 4C and the water -2C, with many survivors stating they felt they could never shift the memory of the cold for the rest of their days. From the point of view of any one of the lifeboats, you have been rowed some few hundred yards from the ship on a sea that was as calm as a millpond. You look back to see the grandest ship ever built listing deeply into the water, looking “like an enormous glow worm, for she was alight from the rising water line clear to the stern – electric lights blazing in every cabin on all the decks and lights at her mast heads…” (On A Sea of Glass). You are looking across the sea, where some way away a ship, which just some 50 minutes ago you were drinking and dancing on, is sinking. You and your fellow passengers are entirely alone, without knowledge of rescue or the fate of your loved ones aboard. As time passes and the chaos increases, soon enough the stern of the ship is 100 feet in the air, the lights go out, and you find yourself now in a pitch-black expanse surrounded by the sounds of chaos, screams, and soon enough explosions. You sit and watch as the ship snaps into two and slowly descends into the water. Everything that should not be happening is happening, and there is nothing that can be done. There was all the order there could have been, complete with notable gallantry and decorum, and yet here still, death abounds and man finds himself entirely helpless.

However, there was one man who didn’t look as she sunk. J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman and director of White Star Line, finding himself aboard a lifeboat turned away from the sinking, and during the inquiry into the sinking had this to say of his actions.

Senator SMITH.

Mr. Ismay, what can you say about the sinking and disappearance of the ship? Can you describe the manner in which she went down?

Mr. ISMAY.

I did not see her go down.

Senator SMITH.

You did not see her go down?

Mr. ISMAY.

No, sir.

Senator SMITH.

How far were you from the ship?

Mr. ISMAY.

I do not know how far we were away. I was sitting with my back to the ship. I was rowing all the time I was in the boat. We were pulling away.

Senator SMITH.

You were rowing?

Mr. ISMAY.

Yes; I did not wish to see her go down.

Senator SMITH.

You did not care to see her go down?

Mr. ISMAY.

No. I am glad I did not.

If there is anything, or more specifically, anyone who has been treated unjustly by filmmakers, writers, and even some Titanic aficionados it is Bruce Ismay. Quickly lambasted by the press, and famously rumored to have dressed up as a woman to escape the ship, Ismay’s life took an inevitable quick turn post-sinking. Thought of as a coward for the mere fact of his surviving whilst being in a position of authority, the truth of the matter is that Ismay helped a lot of people escape the sinking ship, and only got into a lifeboat (with many more spare seats) when ordered to by a crewmember. Upon being rescued by the Carpathia, Ismay appears to have entered into a state of intense shock. Another survivor, Jack Thayer stated “[Ismay] was staring straight ahead, shaking like a leaf. Even when I spoke to him, he paid absolutely no attention. I have never seen a man so completely wrecked.”, noting that he remembered his hair aboard the Titanic as black with flecks of grey, whereas now it was almost entirely white. There are, of course, obvious reasons for his shock and mental collapse, but upon reading How to Survive the Titanic, or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay by Frances Wilson, one comes to understand there’s a second, more psychoanalytical side to this collapse, and that with the sinking of the Titanic equally comes the sinking of every facet of Ismay’s being, these are however biographical details I won’t be delving into here.

As we’ve seen, the hubris argument doesn’t quite stand for the material reality of the Titanic, the reason for its sinking, in factual terms, appears to be no more than a collection of minor anomalies cohering into an unimaginable situation. But we’re modern men, and we need reasons, or at the very least, we need excuses, we need someone to blame. With Ismay, we have our, rather temporary, scapegoat. For where reason has failed us we need a reason as to why; where security has failed us we need to become quickly secure in knowledge as to why; and, where certainty has failed us we have to become certain as to why.

A sunken, defeated, depressed, and shamed figure, the Ismay we see during the inquiry appears to almost disappear into the fabric of the room. And yet, he was cleared of blame and went on to lead a reclusive life, in a depressive state from which he would never emerge. Immediately after the sinking he dealt with Titanic inquiries and problems with great fortitude, but once it was done, he never spoke it again, except once. Less than a year before Ismay's death, one of his grandsons, who had learned Ismay had been involved in maritime shipping, inquired if his grandfather had ever been shipwrecked. Ismay finally broke his quarter-century silence on the tragedy that had blighted his life, replying: "Yes, I was once in a ship which was believed to be unsinkable."

In 1912 Joseph Conrad, in his piece Some Reflections on the Loss of the Titanic, comments on the fate of Ismay - “From a certain point of view the sight of the august senators of a great Power rushing to New York and beginning to bully and badger the luckless "Yamsi"--on the very quay-side so to speak--seems to furnish the Shakespearian touch of the comic to the real tragedy of the fatuous drowning of all these people who to the last moment put their trust in mere bigness, in the reckless affirmations of commercial men and mere technicians and in the irresponsible paragraphs of the newspapers booming these ships!”

Conrad continues - “What are they after? What is there for them to find out? We know what had happened. The ship scraped her side against a piece of ice, and sank after floating for two hours and a half, taking a lot of people down with her. What more can they find out from the unfair badgering of the unhappy "Yamsi," or the ruffianly abuse of the same.”

This all brings us to the odd title of this write-up, ‘Luckless Yamsi’. ‘Yamsi’ (Ismay spelled backward) was Ismay’s attempt to keep the correspondence, that came directly from himself immediately post-sinking, private, especially amidst the shame and blame directed at Ismay as he arrived back in New York. The scapegoat was aware of its status and quickly thought to conceal its identity. Ismay was a businessman and certainly knew of the cynical and bitter side of journalism, and it would have been evident to him that there would have been no better press than the sinking of the unsinkable. The last word in shipbuilding [read: reason] had failed, but there still had to be a…reason, right?

Yet, as Conrad is quick to put forth “What are they after? What is there for them to find out? We know what had happened. The ship scraped her side against a piece of ice, and sank after floating for two hours and a half, taking a lot of people down with her.” The question, then, as to what they were after is caught up in the very specter that sunk alongside the Titanic itself. Luckless Yamsi was the last certainty to survive the sinking of certainty itself. The sinking of the Titanic—with the ship itself being the idealistic amalgamation of size, speed, grandeur, wealth, prosperity, pilgrimage, progress, society, and etiquette—created a literal gulf of symbolic appreciation, wherein all popular optimistic symbols had long since sunk. Ismay arrives as a presumed relic of something now lost, a man who many still (entirely erroneously) believe should have gone down with the ship, the last bastion of an answer where all others were lost. This may appear as a grandiose claim, but I see Ismay as not only trying to defend the loss of the Titanic itself but the very ideals she represented. Ismay was called to the stand in defense of a reason that had already failed. A read of Ismay’s partaking in the inquiry reveals only the utter impotence (as Conrad pointed out) of the situation.

The British inquiry lasted 36 days, with a cost of nearly £20,000 (£1,676,602 at today's prices), it was the longest and most detailed court of inquiry in British history up to that time. And what, exactly, did it ‘prove’? The final report resulted in a detailed description of the ship, an account of the ship's journey, a description of the damage caused by the iceberg, and an account of the evacuation and rescue. In truth, then, it resulted in much information we already knew, with a detailed addendum concerning the fact the ship sunk. To repeat Conrad, “What is there for them to find out?” and as such, I shall state, that if there is any hubris relating to the event of the Titanic in its entirety, it is the inquiry itself. It resulted, yes, in greater safety measures. But these were not measures that arose from regulatory negligence. The hubris, in a question then, is to ask - as per the inquiry - how could this have happened? To which the truthful answer is quite simple, but the realistic answer is not one that anyone wishes to hear. That reason failed.

To return to the question then, of what exactly sank that night, the ‘thing’ that haunts us, appears to be not something that was lost, but something that arrived. It is clear there was something else that entered our collective unconscious as the ship ached, and sank, and the story became a sensation. A specter arose as the unsinkable sunk. For the unsinkable is certain, that which shall never be and thus is universal. What it was that the survivors noted in the quiet phrase ‘She’s gone.’ as the stern bubbled under the surface, what Ismay could not face, was the arrival of the relative nature of all our creations, the impermanence of all things despite our literal best efforts. The odd banality of doing everything right and still having to accept failure.

(Titanic departing Southampton on 10 April 1912)

The Ship of Dreams, the Queen of the Ocean, the RMS Titanic, alive for 13 days. The epitome of modernity. A floating testament to splendor, wealth, courtesy, and class. A symbol of what it is to conquer and control. Holding every man and every woman, immigrant or national, homebound or pilgrim. Iron against ice with a resulting six dashes against its hull, a fatal Morse code. From afar they must have looked as panicked ants as Nearer, My God, to Thee was carried gently across the water. Little rockets light the sky, pinpricks of light trying to fight an eternal black. Sometime later, a mere 2 and a half hours and she’s bellowing, aching, resounding out from a black abyss as the screams of 1500 surround. Ripped into two, implosions from the deep ring out. One half glides as the other half heads into a violent spin, landing a mile apart they shall forever be separated in complete darkness. Slowly, slowly, the screams die out to the last, as a handful of lifeboats await to be rescued

(Lifeboat 6 rowing towards RMS Carpathia on April 15, 1912)

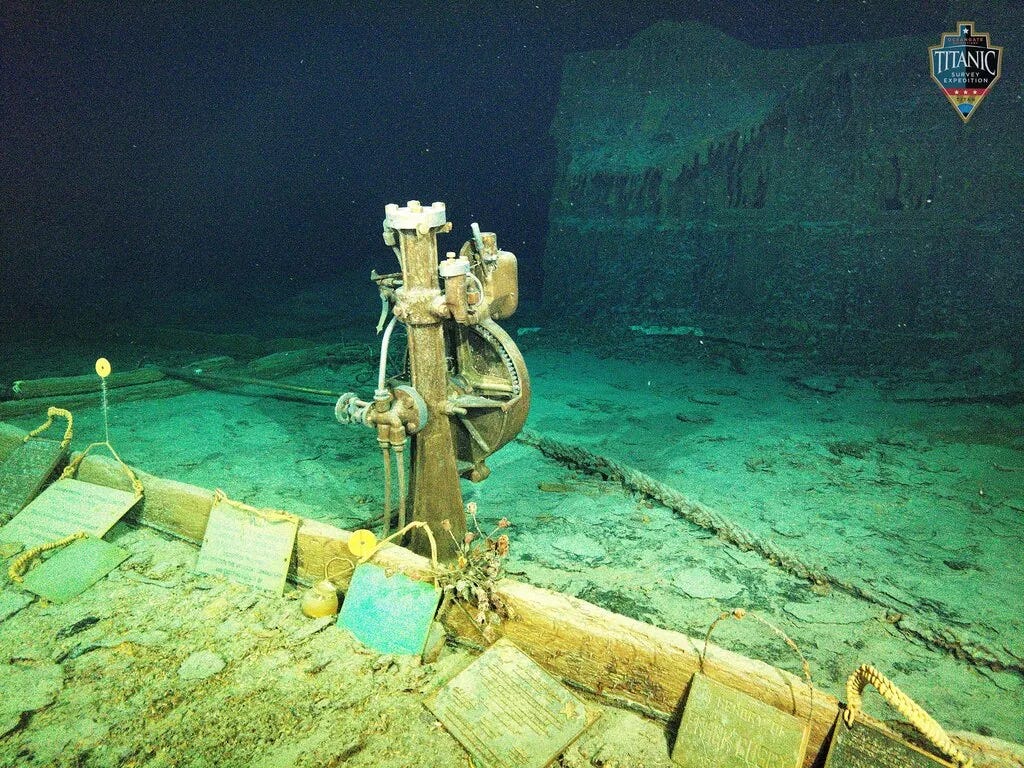

The wreck sits some 12,500 feet below sea level, in a place that shall never see the smallest glimpse of natural light. That once beautiful ship sits eternally fractured in absolute darkness. One day in 1985, some 73 years after the sinking, a small unmanned craft called Argo happened upon it under the direction of Robert Ballard. And as if from nowhere, one can imagine the gargantuan, hulk of a wreck appearing from the deep, a titan consumed by the sea. Soon enough she will be gone, with estimates ranging from 15 to 100 years until the wreck is consumed entirely, and all that is left of this tragedy is a rust stain on the sea floor, forgotten forever more.

(The Titanic’s telemotor. Image credit: OceanGate Expeditions)

Bibliography:

Some Reflections on the Loss of the Titanic, Joseph Conrad

A Night to Remember, 1955, Walter Lord

The Ship of Dreams, 2019, Gareth Russell

On a Sea of Glass, 2012, Fitch, Layton, Wormstedt

How to Survive the Titanic, or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay, 2011, Frances Wilson

Beautiful essay. Thank you

Yes, kinda like Key 16. Just with ice rather than feu en ciel.

Lemurian pushback.